Colin Alexander Hanna and Pricie Hanna, Price Hanna Consultants01.04.19

The millennial wave (of parents) is impacting the baby diaper market in the U.S., and it is unlike any previous wave. Millennials approach parenting, and the shopping that comes with it, with a different set of priorities and way of evaluating products. A new crop of startup companies founded by millennials has emerged to lead the way in showing how to position baby diapers in ways that appeal most to millennial parents. More recently, there are plenty of examples of the leading brands employing these same strategies.

Since 2016, more than one million millennials in the U.S. are becoming first-time moms each year. Nearly 90% of births in 2017 were to millennial moms so, to baby diaper brands, millennial parents are a critical consumer segment focal point.

Millennials are generally understood to be Americans between the ages of 25 and 37. As parents, they are older and more educated than their predecessors. According to data tracked by the CDC, the average age of first-time mothers in the U.S. was 28 in 2018, compared to 25 in 1970. Millennials are more educated than previous generations, and the most educated women have seen the most dramatic increases in motherhood.

Millennial parents are also choosing to have fewer babies. America’s fertility rate reached an all-time low of 1.8 in 2018, which is below the “replacement level” estimated for developed countries of 2.1. A recent survey conducted by the Morning Consult for The New York Times found that a majority of adults in America between ages 20 to 45 said they “planned to have fewer children than their parents.”

While millennials plan to have fewer children, they devote more time to parenting than previous generations. Pew Research Center found that moms spent about 25 hours a week on paid work in 2016, compared with nine hours in 1965. Despite the increased demand of time spent working, mothers also managed to spend 14 hours a week directly caring for their children, which was more than the 10 hours moms devoted on average to child care in 1965. Millennial dads chip in a lot more too these days, spending an average of 8 hours a week of their time on child care in 2014, compared to just 2.5 hours in 1965.

Millennial parents derive a strong sense of identity from being good parents. A 2010 Pew Research Center survey found that 52% said being a good parent was one of the most important goals in their lives, compared to 30% who said the same about having a successful marriage.

One parenting research expert, Rebecca Parlakian of the parent and early childhood advocacy organization Zero-to-Three, describes millennial parents as “high-information parents.” Ipsos research found that 86% of millennial dads turn to YouTube for “guidance on key parenting topics,” and three in four of all millennial parents say they are open to videos by brands or companies on YouTube when “seeking guidance on parenting topics.”

Millennials also shop differently. A survey conducted by the National Retail Federation found that millennial parents are much more likely than other parents to 1) use their smartphones to research products (78% millennial parents; 58% other parents), 2) use a same-day shipping option (86% millennial parents; 67% other parents), and 3) use a subscription service as part of their online shopping (40% millennial parents; 18% other parents).

Millennial parents not only want to know more about the products they purchase, they also want to know more about the companies and brands they are supporting with each purchase. When Forbes conducted a broad survey of millennials in March 2018, they found that “60% of millennials tend to gravitate toward purchases that are an expression of their personality – the brand must speak to them and make them feel good.” Euclid surveyed 1,500 U.S. consumers and found that, among millennials, 52% were more inclined to purchase from brands that mirrored their values and politics, compared to just 35% of baby boomers.

What do all these insights into the characteristics and motivations of millennial parents mean for the baby diapers industry? While the demographic and behavioral trends suggest the need for new approaches by baby diaper brands to deliver value and earn longer-term customer loyalty; technological developments in e-commerce, logistics, manufacturing and supply chain management have made conditions more inviting to a new host of startup companies to enter the baby diaper market.

E-commerce Baby Diaper Startups: Lower Barriers to Entry, High Barriers to Trust

The combination of affordable costs to design a website and e-commerce platform, access to contract manufacturing and a competitive ocean of low-cost third-party fulfillment and logistics providers are making longstanding barriers to entry in the baby diaper industry less relevant. These new entrants into the baby diaper market have employed innovative marketing strategies, product designs and value propositions to build a foothold in the industry, to the point that major leaders and their brands are now replicating these same strategies to maximize their appeal to millennial parents.

One lesson these startup companies reveal is millennial parents’ trust must be hard-won before they become brand-loyal. Millennial parents do not assume products designed for their babies are safe. They also are skeptical about products that do not disclose their ingredients. Millennial parents able to afford premium diapers demand and prioritize safety and transparency over concerns such as environmental impact and sustainability.

The Honest Company provides an illustrative example of an internet startup founded by a millennial parent for millennial parents who share these concerns. Furthermore, it is an example of a company that continues to find ways to grow its share and evolve its product offering. The Honest Co. was founded by celebrity actress Jessica Alba in 2012 as her response to an allergic reaction to detergent suffered by her first child. The company began selling goods via a subscription model on its own website and has since grown to add broad distribution through retail brick-and-mortar channels and Amazon.

In founding the company, Alba expressed her concern about what she perceived as toxic petrochemicals not from an environmental friendliness perspective, but from a parent wanting safety above all from any product touching her baby’s skin. Her mission: “I wanted safe and effective consumer products that were beautifully designed, accessibly priced, and easy to get.”

Implementation of this mission hit a snag when, in 2016, reports surfaced and lawsuits followed due to false claims The Honest Co. had made when sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) was found in its detergent and in its “organic” infant formula was found to contain synthetic substances prohibited by federal law for organic products. Topping it off, in late 2016, reports surfaced regarding a tidal wave of consumer complaints that had been filed with the Federal Trade Commission about consumers’ difficulty processing cancellation requests to its diaper subscription service. The Honest Co. responded promptly to all of these problems by redesigning its products and adding an easier online cancellation process for its diaper subscription service.

For its baby diapers, The Honest Co. was one of the first brands not only to specify the ingredients of its diapers, but also to disclose where they were sourced. As they increased their transparency, they also found they needed to better meet customer expectations for diaper performance. Millennial parents are like all other parent consumers of baby diapers in one respect: no-leak performance/reliability is a must. In 2018, The Honest Co. introduced an upgraded diaper design, featuring a TrueAbsorb core. Delivering a more absorbent diaper meant finding a new source, while maintaining a commitment to transparency and sustainability. They switched from sourcing corn starch-mixed superabsorbent from “Texas and Quebec, Canada,” to a superabsorbent that incorporates “renewable materials” from “the U.S. and Belgium.” The Honest Co. diapers are made in Mexico.

A much more recent entrant to the baby diaper market, Made Of, promises an even greater degree of transparency regarding all the materials and processes involved in manufacturing its diapers. The brand’s website delivers what is called Ultimate Transparency Promise: “We’ve made our products, factories and our formulas to be totally open to you. Click on any product page and get every element and the whole story.”

The baby diaper page, however, falls a bit short of this promise. After scrolling down several pages, when you click on “superabsorbent polymer,” your see merely “Partially neutralized sodium polyacrylate. Made in USA.” Then when you click “View Ingredient Details,” the internet shopper is greeted with “At this point there is no document downloaded for this element.” The same is true for the “transfer layer,” “poly lines” and “nonwoven back side panels,” which are also “Made in USA;” and the “topsheet,” “backsheet,” “nonwoven side panels” and “adhesives, tabs.” The diapers are “Made in Mexico.” Made Of’s “Better Diaper” does bear an impressive slate of material certifications and partnerships, including PEFC certified forest products, Rainforest Alliance, Social Accountability 8000, and ISO 9001’s certification for quality management systems; with images of certificates for each one.

While safety and transparency are the must-haves after basic reliability and performance expectations, what about the overall experience for the parent who not only buys the diapers, but regularly gets the honor of changing the diapers? Parasol is another by-millennials-for-millennials startup brand that strives to design diapers that deliver a higher level of satisfaction not only for the baby, but also for the parent. This super-premium quality diaper is made in China. The diaper features an ultra soft, 3D apertured topsheet, a thin pulp-less core made with a soft layered nonwoven/superabsorbent sandwich and a soft apertured nonwoven outer cover over a quiet, soft barrier film with a high fashion design pattern. Millennial parents, perhaps more than previous generations, really value additional levels of personalization and customizability featured in otherwise commodity products. Deloitte Consumer Review conducted research in 2015 that supports this strategy. They found that about one in five consumers was willing to pay an up to 20% premium for products with a greater degree of personalization.

As noted above, millennials also want to feel connected and aligned with the values held by the brand of diapers they buy for their babies. That’s been the main focus of startups like ABBY&FINN, whose stated mission is as follows: “We truly seek to improve the lives of the children & families we touch by partnering with organizations that use diapers as incentives for participating in parenting & child wellness programs. It’s so important, it’s literally in our name.” The “ABBY” part of the name is an anagram for BABY, and the “FINN” is an acronym for “Families in need.” They offer a diaper subscription service where “with each monthly box subscription, we donate a diaper a day to families in need. That means every time you receive a box, we are donating 30 diapers right here in the U.S.” Attuned supply chain partners will also seek to capture value from their part in products and brands that promote positive social causes. Symbia Logistics proudly announced, “ABBY&FINN chose Symbia thanks to our reliability, customization, fair pricing and a reputation for getting the job done right – which, as it turns out, are the very same reasons they’re growing.” Raw materials and components suppliers should seek opportunities to do the same.

When it comes to the diapers, ABBY&FINN are positioned much the same way as The Honest Co., Parasol, and Made Of, with a detailed list of ingredients included, as well as a list of the “harmful substances” not included in their diapers. Staying true to the values held by most millennial parents, founders Amanda and Lance Little “developed a business model that brings design-oriented, eco-friendly, premium diapers to your door, and donates 30 diapers to families-in-need.” Although this company does not disclose where the diapers are made, their appearance is very similar to the Made Of diapers that are made in Mexico.

It is difficult to conclude with certainty whether diaper brands like Parasol, Made Of and ABBY&FINN will successfully grow their business enough to expand distribution to brick-and-mortar retail channels the way The Honest Co. has managed to do with its diapers.

Reliable market share data for e-commerce sales is not yet available the way it is for brick-and-mortar retail sales. The strongest evidence for why the concerns and appetites of millennial parents outlined above represent a significant consumer segment, and why the strategies innovatively employed by these startups are effective forms of appeal, is that the major brand leaders imitate these same strategies.

Since 2016, more than one million millennials in the U.S. are becoming first-time moms each year. Nearly 90% of births in 2017 were to millennial moms so, to baby diaper brands, millennial parents are a critical consumer segment focal point.

Millennials are generally understood to be Americans between the ages of 25 and 37. As parents, they are older and more educated than their predecessors. According to data tracked by the CDC, the average age of first-time mothers in the U.S. was 28 in 2018, compared to 25 in 1970. Millennials are more educated than previous generations, and the most educated women have seen the most dramatic increases in motherhood.

Millennial parents are also choosing to have fewer babies. America’s fertility rate reached an all-time low of 1.8 in 2018, which is below the “replacement level” estimated for developed countries of 2.1. A recent survey conducted by the Morning Consult for The New York Times found that a majority of adults in America between ages 20 to 45 said they “planned to have fewer children than their parents.”

While millennials plan to have fewer children, they devote more time to parenting than previous generations. Pew Research Center found that moms spent about 25 hours a week on paid work in 2016, compared with nine hours in 1965. Despite the increased demand of time spent working, mothers also managed to spend 14 hours a week directly caring for their children, which was more than the 10 hours moms devoted on average to child care in 1965. Millennial dads chip in a lot more too these days, spending an average of 8 hours a week of their time on child care in 2014, compared to just 2.5 hours in 1965.

Millennial parents derive a strong sense of identity from being good parents. A 2010 Pew Research Center survey found that 52% said being a good parent was one of the most important goals in their lives, compared to 30% who said the same about having a successful marriage.

One parenting research expert, Rebecca Parlakian of the parent and early childhood advocacy organization Zero-to-Three, describes millennial parents as “high-information parents.” Ipsos research found that 86% of millennial dads turn to YouTube for “guidance on key parenting topics,” and three in four of all millennial parents say they are open to videos by brands or companies on YouTube when “seeking guidance on parenting topics.”

Millennials also shop differently. A survey conducted by the National Retail Federation found that millennial parents are much more likely than other parents to 1) use their smartphones to research products (78% millennial parents; 58% other parents), 2) use a same-day shipping option (86% millennial parents; 67% other parents), and 3) use a subscription service as part of their online shopping (40% millennial parents; 18% other parents).

Millennial parents not only want to know more about the products they purchase, they also want to know more about the companies and brands they are supporting with each purchase. When Forbes conducted a broad survey of millennials in March 2018, they found that “60% of millennials tend to gravitate toward purchases that are an expression of their personality – the brand must speak to them and make them feel good.” Euclid surveyed 1,500 U.S. consumers and found that, among millennials, 52% were more inclined to purchase from brands that mirrored their values and politics, compared to just 35% of baby boomers.

What do all these insights into the characteristics and motivations of millennial parents mean for the baby diapers industry? While the demographic and behavioral trends suggest the need for new approaches by baby diaper brands to deliver value and earn longer-term customer loyalty; technological developments in e-commerce, logistics, manufacturing and supply chain management have made conditions more inviting to a new host of startup companies to enter the baby diaper market.

E-commerce Baby Diaper Startups: Lower Barriers to Entry, High Barriers to Trust

The combination of affordable costs to design a website and e-commerce platform, access to contract manufacturing and a competitive ocean of low-cost third-party fulfillment and logistics providers are making longstanding barriers to entry in the baby diaper industry less relevant. These new entrants into the baby diaper market have employed innovative marketing strategies, product designs and value propositions to build a foothold in the industry, to the point that major leaders and their brands are now replicating these same strategies to maximize their appeal to millennial parents.

One lesson these startup companies reveal is millennial parents’ trust must be hard-won before they become brand-loyal. Millennial parents do not assume products designed for their babies are safe. They also are skeptical about products that do not disclose their ingredients. Millennial parents able to afford premium diapers demand and prioritize safety and transparency over concerns such as environmental impact and sustainability.

The Honest Company provides an illustrative example of an internet startup founded by a millennial parent for millennial parents who share these concerns. Furthermore, it is an example of a company that continues to find ways to grow its share and evolve its product offering. The Honest Co. was founded by celebrity actress Jessica Alba in 2012 as her response to an allergic reaction to detergent suffered by her first child. The company began selling goods via a subscription model on its own website and has since grown to add broad distribution through retail brick-and-mortar channels and Amazon.

In founding the company, Alba expressed her concern about what she perceived as toxic petrochemicals not from an environmental friendliness perspective, but from a parent wanting safety above all from any product touching her baby’s skin. Her mission: “I wanted safe and effective consumer products that were beautifully designed, accessibly priced, and easy to get.”

Implementation of this mission hit a snag when, in 2016, reports surfaced and lawsuits followed due to false claims The Honest Co. had made when sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) was found in its detergent and in its “organic” infant formula was found to contain synthetic substances prohibited by federal law for organic products. Topping it off, in late 2016, reports surfaced regarding a tidal wave of consumer complaints that had been filed with the Federal Trade Commission about consumers’ difficulty processing cancellation requests to its diaper subscription service. The Honest Co. responded promptly to all of these problems by redesigning its products and adding an easier online cancellation process for its diaper subscription service.

For its baby diapers, The Honest Co. was one of the first brands not only to specify the ingredients of its diapers, but also to disclose where they were sourced. As they increased their transparency, they also found they needed to better meet customer expectations for diaper performance. Millennial parents are like all other parent consumers of baby diapers in one respect: no-leak performance/reliability is a must. In 2018, The Honest Co. introduced an upgraded diaper design, featuring a TrueAbsorb core. Delivering a more absorbent diaper meant finding a new source, while maintaining a commitment to transparency and sustainability. They switched from sourcing corn starch-mixed superabsorbent from “Texas and Quebec, Canada,” to a superabsorbent that incorporates “renewable materials” from “the U.S. and Belgium.” The Honest Co. diapers are made in Mexico.

A much more recent entrant to the baby diaper market, Made Of, promises an even greater degree of transparency regarding all the materials and processes involved in manufacturing its diapers. The brand’s website delivers what is called Ultimate Transparency Promise: “We’ve made our products, factories and our formulas to be totally open to you. Click on any product page and get every element and the whole story.”

The baby diaper page, however, falls a bit short of this promise. After scrolling down several pages, when you click on “superabsorbent polymer,” your see merely “Partially neutralized sodium polyacrylate. Made in USA.” Then when you click “View Ingredient Details,” the internet shopper is greeted with “At this point there is no document downloaded for this element.” The same is true for the “transfer layer,” “poly lines” and “nonwoven back side panels,” which are also “Made in USA;” and the “topsheet,” “backsheet,” “nonwoven side panels” and “adhesives, tabs.” The diapers are “Made in Mexico.” Made Of’s “Better Diaper” does bear an impressive slate of material certifications and partnerships, including PEFC certified forest products, Rainforest Alliance, Social Accountability 8000, and ISO 9001’s certification for quality management systems; with images of certificates for each one.

While safety and transparency are the must-haves after basic reliability and performance expectations, what about the overall experience for the parent who not only buys the diapers, but regularly gets the honor of changing the diapers? Parasol is another by-millennials-for-millennials startup brand that strives to design diapers that deliver a higher level of satisfaction not only for the baby, but also for the parent. This super-premium quality diaper is made in China. The diaper features an ultra soft, 3D apertured topsheet, a thin pulp-less core made with a soft layered nonwoven/superabsorbent sandwich and a soft apertured nonwoven outer cover over a quiet, soft barrier film with a high fashion design pattern. Millennial parents, perhaps more than previous generations, really value additional levels of personalization and customizability featured in otherwise commodity products. Deloitte Consumer Review conducted research in 2015 that supports this strategy. They found that about one in five consumers was willing to pay an up to 20% premium for products with a greater degree of personalization.

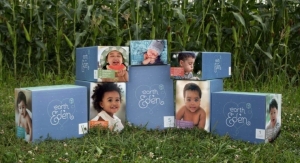

As noted above, millennials also want to feel connected and aligned with the values held by the brand of diapers they buy for their babies. That’s been the main focus of startups like ABBY&FINN, whose stated mission is as follows: “We truly seek to improve the lives of the children & families we touch by partnering with organizations that use diapers as incentives for participating in parenting & child wellness programs. It’s so important, it’s literally in our name.” The “ABBY” part of the name is an anagram for BABY, and the “FINN” is an acronym for “Families in need.” They offer a diaper subscription service where “with each monthly box subscription, we donate a diaper a day to families in need. That means every time you receive a box, we are donating 30 diapers right here in the U.S.” Attuned supply chain partners will also seek to capture value from their part in products and brands that promote positive social causes. Symbia Logistics proudly announced, “ABBY&FINN chose Symbia thanks to our reliability, customization, fair pricing and a reputation for getting the job done right – which, as it turns out, are the very same reasons they’re growing.” Raw materials and components suppliers should seek opportunities to do the same.

When it comes to the diapers, ABBY&FINN are positioned much the same way as The Honest Co., Parasol, and Made Of, with a detailed list of ingredients included, as well as a list of the “harmful substances” not included in their diapers. Staying true to the values held by most millennial parents, founders Amanda and Lance Little “developed a business model that brings design-oriented, eco-friendly, premium diapers to your door, and donates 30 diapers to families-in-need.” Although this company does not disclose where the diapers are made, their appearance is very similar to the Made Of diapers that are made in Mexico.

It is difficult to conclude with certainty whether diaper brands like Parasol, Made Of and ABBY&FINN will successfully grow their business enough to expand distribution to brick-and-mortar retail channels the way The Honest Co. has managed to do with its diapers.

Reliable market share data for e-commerce sales is not yet available the way it is for brick-and-mortar retail sales. The strongest evidence for why the concerns and appetites of millennial parents outlined above represent a significant consumer segment, and why the strategies innovatively employed by these startups are effective forms of appeal, is that the major brand leaders imitate these same strategies.